Measured head-to-head against central bank-issued national currencies in terms of market value, cryptocurrencies still represent a drop in the ocean. But cryptos’ rapid ascent to prominence is making some central bankers very nervous.

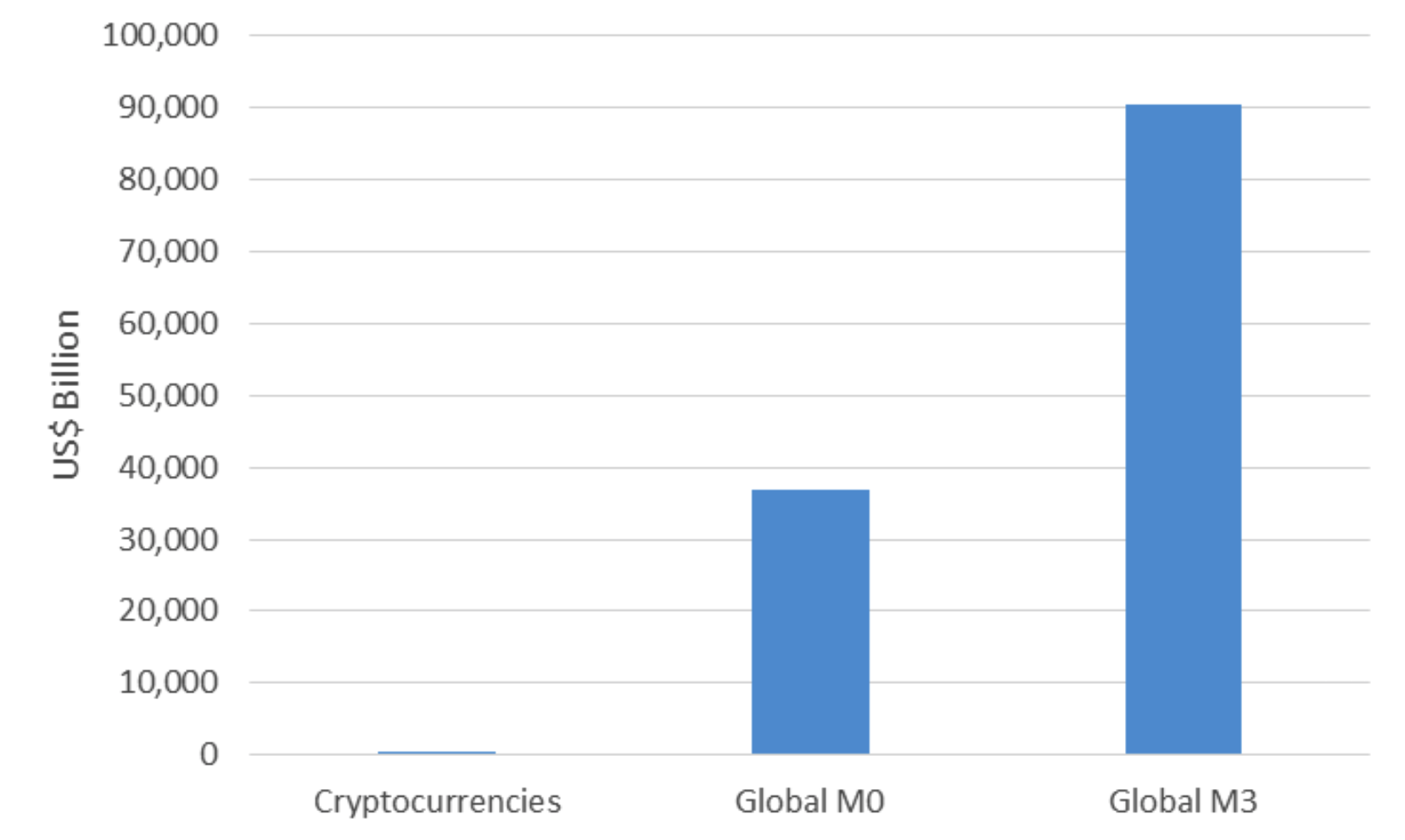

At the beginning of March 2018, according to coinmarketcap.com, cryptocurrencies’ combined market value was around $450 billion, with bitcoin representing around 40 percent of the total. That’s still way short of the $37 trillion represented by the world’s coins, banknotes and other cash-like instruments (also known as “M0”).

The broader, “M3” measure of global money supply, which includes cash, near-cash, current and savings accounts, time deposits and money market funds, is $90 trillion, 200 times the size of the cryptocurrency market.

A drop in the monetary ocean – cryptocurrencies in context

Source: Coinmarketcap.com, the Money Project

But despite their tiny footprint, these new currencies still appear to be ruffling central bankers’ feathers. The governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, devoted a 30 minute-speech in early March to a detailed critique of cryptocurrencies’ ability to serve as money, before concluding that they are not up to the job.

“The long, charitable answer is that cryptocurrencies act as money, at best, only for some people and to a limited extent, and even then only in parallel with the traditional currencies of the users. The short answer is they are failing,” said Carney.

“Bitcoin is a combination of a bubble, a Ponzi scheme and an environmental disaster”.

Carney’s comments mirror those of the Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) general manager Agustín Carstens, made a month earlier. The BIS is often described as the “central bankers’ central bank” since it acts as their primary forum for discussion, policy analysis and information-sharing.

In a February speech Carstens described bitcoin as “a combination of a bubble, a Ponzi scheme and an environmental disaster”.

Are cryptocurrencies money?

Central bankers appear to have decided to address the cryptocurrency threat head-on, focusing on what they see as the new currencies’ lack of utility as money. In his speech, referring to the three textbook definitions of money, Carney asserted that cryptocurrencies are a poor store of value, an inefficient medium of exchange and a virtually non-existent unit of account.

Carney’s attack on cryptocurrencies’ use as a store of value was twofold. First, he said, their price volatility makes them unsuitable for saving. Second, he argued, the fixed money supply inherent in currencies like bitcoin is a serious deficiency.

“Fundamentally, [cryptocurrencies] would impart a deflationary bias on the economy if…widely adopted. Recreating a virtual global gold standard would be a criminal act of monetary amnesia,” said Carney.

Carney said that a fixed money supply could harm the economy by contributing to deflation in the prices of goods, services and wages. And, he added, the inability of the money supply to vary in response to demand would likely cause greater volatility in prices and real activity.

By contrast, many bitcoin advocates argue that a return to a relatively fixed money supply, such as under the gold standard, is a desirable objective, rather than something to be feared.

“The era of the classical gold standard, from 1871—the end of the Franco-Prussian War until the beginning of World War I—was known as the Golden Era, the Gilded Age, and La Belle Epoque,” said Dr. Saifedean Ammous, assistant professor of economics at the Lebanese American University, in a recent interview given to the Epoch Times.

“It was a time of unrivalled human flourishing all over the world. Economic growth was everywhere. Technology was being spread all over the world. Peace and prosperity were increasing everywhere around the world. Technological innovations were advancing.”

Ammous believes that the forthcoming adoption of bitcoin as a monetary standard has a direct parallel in history—the introduction of the Byzantine solidus, a gold coin of fixed weight and purity—in the 4th century AD under Emperors Diocletian and Constantine.

“Satoshi Nakamoto is our Constantine, Bitcoin is his solidus, and the internet is our Constantinople.”

Following two centuries of currency debasement and political turbulence in the late Roman empire, the introduction of the solidus heralded seven centuries of monetary stability and flourishing economic growth in the Eastern Mediterranean, centred on Constantine’s capital—Byzantium (later Constantinople and now Istanbul).

“If the modern world is ancient Rome, Satoshi Nakamoto is our Constantine, Bitcoin is his solidus, and the internet is our Constantinople,” Ammous wrote in a tweet last year.

Larry White, professor of economics at George Mason University, criticises central bankers’ portrayal of deflation as something to be avoided at all costs.

“The argument that deflation is bad per se is a very weak one,” said White in a telephone interview with New Money Review.

“You can have both benign and harmful deflation. Harmful deflation happens when the money supply shrinks, or when people are hoarding money. It’s not harmful to have prices fall because output is growing faster than the supply of money. Under the gold standard, falling prices were typically not linked to recessions, in the sense of real output falling.”

The Bank of England’s Carney and BIS general manager Carstens also argue that cryptocurrencies are unsuitable as a medium of exchange and a unit of account—the other two of the three textbook definitions of money.

“Currently, no major high street or online retailer accepts Bitcoin as payment in the UK, and only a handful of the top 500 US online retailers do,” said Carney.

“For those who can find someone willing to accept payment for goods and services in cryptocurrencies, the speed and cost of the transaction varies but it is generally slower and more expensive than payments in sterling.”

“Given that they are poor stores of value and inefficient and unreliable media of exchange, it is not surprising that there is little evidence of cryptocurrencies being used as units of account.”

“Money has always evolved in stages, with the store of value role preceding the medium of exchange role.”

But central bankers’ broadside against cryptocurrencies fails to recognise that these new moneys are likely to serve different functions at different stages of their evolution, argues Vijay Boyapati, a US-based software engineer.

“Many have criticized Bitcoin as being an unsuitable money because its price has been too volatile to be suitable as a medium of exchange. This puts the cart before the horse, however. Money has always evolved in stages, with the store of value role preceding the medium of exchange role,” wrote Boyapati in a recent article on Medium.

“It will likely be several years before Bitcoin transitions from being an incipient store of value to being a true medium of exchange. It is striking to note that the same transition took many centuries for gold.”

Meanwhile, the real reason for central bankers’ nervousness about bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies is that it threatens their hold on the monetary reins of power, says Pascal Bouvier, venture partner at Santander Innoventures.

“The borderline hysteria exhibited by most if not all central banks, financial regulators and various governments [to the emergence of cryptocurrencies] is a very normal and expected reaction. It’s borne out of fear on the one hand, and outrage at what is perceived, rightly so, as an existential challenge,” Bouvier wrote in February.

The US dollar has lost more than 96% of its purchasing power since the inception of the Federal Reserve Bank in 1913 – how’s that for “store of value”? The British Pound has lost value if measured in US Dollars, so it’s track record is even worse.

Central Banks try to avoid deflation at any cost. They know that banks would collapse during prolonged periods of deflation, as debt would remain same in nominal terms while assets would fall (resulting in losses for banks). But this is only due to the fact banks use leverage.

Nobody will claim that price deflation in the technology sector has put the monetary system in danger. I can order a replacement camera for the iPhone for 6 Euros, while a much inferior digital camera in 1997 cost 200 Euros.

However, one has to admit that salaries are much ‘stickier’ as it is hard to convince employees to accept pay cuts in times of deflation (even if their real income would rise). So while deflation in technology-heavy sectors can be positive I have sympathy for the idea deflation could be dangerous for employment in service-heavy sectors.

Still, any system with an inflation bias is punishing savers while rewarding indebtedness. If you believe that I = S (investment equals savings), a saver-unfriendly environment could lead to lack of investment in the longer run. Neglected infrastructure and / or slowing rate of innovation would be the consequence, as can be witnessed in the US.