The BIS says the underpinning of trust in cryptocurrencies like bitcoin is fragile. Cryptocurrency supporters argue the opposite—past glitches have helped make bitcoin stronger than ever.

‘The underpinning of trust in cryptocurrencies is fragile’

In the chapter it devotes to cryptocurrencies in its latest annual report, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) levels some familiar criticisms: it says cryptocurrencies waste energy, their prices are volatile and their settlement of money transfers is never 100 percent guaranteed.

But the BIS also takes aim at the technical foundations of cryptocurrencies, arguing that these are more fragile than they appear.

Should cryptocurrency blockchains fail to work as intended, the BIS argues, those holding currency tokens risk a terminal loss of trust and value. Blockchains process sets of transactions in successive files (or ‘blocks’), leading to a supposedly immutable record of a currency’s past dealings.

“Not only is the trust in individual payments uncertain, but the underpinning of trust in each cryptocurrency is also fragile. This is due to ‘forking’,” says the BIS.

In a cryptocurrency fork, a subset of cryptocurrency holders coordinate on using a new version of the ledger and protocol, while others stick to the original one.

Under a so-called soft fork, a currency’s protocol changes in a way that recognises earlier blocks as valid. A hard fork means that that the software enforcing the old rules will not recognise blocks adhering to the new rules.

“Forking may only be symptomatic of a fundamental shortcoming: the fragility of the decentralised consensus involved in updating the ledger and, with it, of the underlying trust in the cryptocurrency,” the BIS says.

Bitcoin’s March 2013 soft fork

To illustrate its concerns, the BIS cites an episode five years ago when bitcoin underwent an unplanned soft fork.

As a result of an erroneous software upgrade, on 11 and 12 March 2013 the network of bitcoin nodes split into two camps: one running according the pre-upgrade rules, the other incorporating the change.

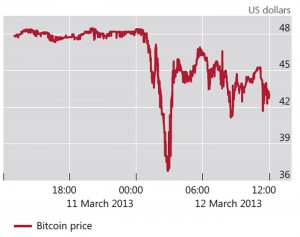

For several hours, the two blockchains operated in parallel. The resulting confusion led to a sharp, 25 percent decline in bitcoin’s price (at around $40, just over half a percent of today’s bitcoin value).

Bitcoin price during 2013 temporary fork

The fork was eventually reversed after coordinated action by bitcoin software developers, helping restore confidence in the network.

However, says the BIS, the need for human intervention witnessed during this episode runs counter to a central claim made cryptocurrency proponents: that currencies like bitcoin achieve trust by decentralised means.

“This episode shows just how easily cryptocurrencies can split, leading to significant valuation losses,” the BIS concludes in its report.

Machine or human consensus?

According to Arvind Narayanan, an assistant professor of computer science at Princeton University, there is a need for occasional external intervention in a cryptocurrency’s development.

“The incident shows the necessity of an effective consensus process for the human actors in the bitcoin ecosystem,” Narayanan wrote in a blog analysing the 2013 soft fork.

Pointing to the crucial role of bitcoin core software developers in identifying and fixing the bug, Narayanan draws a sharp contrast with the image of a cryptocurrency operating on autopilot.

“Contrary to the view of the consensus protocol as fixed in stone by Satoshi [Nakamoto], it is under active human stewardship, and the quality of that stewardship is essential to its security,” Narayanan says.

“Centralised decision-making saved the day here, and for the most part it’s not in conflict with the decentralised nature of the network itself. The human element becomes crucial when the code fails or needs to adapt over time.”

The first bitcoin core developer to spot the potential dangers of the 2013 fork, Luke Dashjr, argues that the quality of decision-making around the network has since improved.

“Nowadays, we have a heightened awareness of the issues that can affect consensus, and take greater care to ensure consensus is not broken unexpectedly,” Dashjr told New Money Review.

Chaos at EOS

Unscripted human intervention in cryptocurrencies seems likely to continue to generate controversy, however.

On June 17, the 21 block producers in charge of validating transactions on the EOS blockchain decided to freeze seven accounts, apparently in response to a phishing scam. The EOS blockchain only went live three days earlier.

Under the EOS consensus model, block producers, who receive monetary rewards, are appointed by token holders after a vote. By contrast, under the bitcoin model block rewards are earned by those devoting sufficient computer processing power to win a form of guessing game.

According to the MIT Technology Review, the governance of the newer cryptocurrency is in near-chaos.

“EOS’s governing constitution hasn’t been ratified yet,”MIT Technology Review wrote on June 21.

“Without a founding document in place, things unraveled when a group of block producers asked the ‘EOS Core Arbitration Forum’, a body that is supposed to function as the network’s judicial branch, to freeze the compromised accounts,” MIT said.

“The forum initially refused, saying it lacked the authority under the interim constitution. So the block producers went ahead and froze the accounts themselves. So much for decentralisation.”

EOS’s token price, however, seems oblivious to the controversy. At around $10.4, it is unchanged from the launch date.

Fragility or antifragility?

Rather than seeing accidental soft forks and human intervention as a sign of potential systemic weakness, some bitcoin proponents argue the opposite: the more bugs bitcoin overcomes, the stronger it proves itself.

“Machine consensus failures are always a possibility,” Jameson Lopp, an infrastructure engineer at Casa, told New Money Review.

“But I’d argue that they demonstrate the antifragility of the network,” Lopp adds.

“It’s the individual humans who comprise the network that make it robust. Running nodes is pointless unless they are backed by human operators.”

The term ‘antifragility’ was popularised in a 2012 book by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a former options trader turned author and academic.

Wikipedia describes antifragility as ‘a property of systems that increase in capability, resilience, or robustness as a result of stressors, shocks, volatility, noise, mistakes, faults, attacks, or failures’.

Lopp cites other evidence of bitcoin’s antifragility: he points out that the cryptocurrency is under near-constant attack from potential adversaries. In turn, he sees this as a net positive for the network, rather than a cause for concern.

In a tweet published on June 20, Lopp wrote that “bitcoin is an adversarial network; by my count there were 68 attempts in the past week to feed an invalid block to my node. There was also an attempt to create 234,512 BTC out of thin air. This is why we don’t trust, we verify.”

“There’s a virtuous evolutionary cycle in security”

Danny Masters, co-founder of digital asset management firm Global Advisors, argues that bitcoin’s open-source software makes it more resilient than traditional financial networks.

“The fact that attacks on digital assets are so ubiquitous and constant means the ecosystem only gathers strength as you successively attack it,” Masters told New Money Review.

“The code supporting digital assets is open-source, so it’s had to develop security characteristics very quickly to survive. There’s a virtuous evolutionary cycle in security.”

One computer scientist questions whether the BIS is being even-handed in its allegations of systemic weaknesses in cryptocurrencies.

“Can we trust ‘money’ that is just an entry in a bank ledger?”

“Is the BIS sufficiently critical of the fact that the population is increasingly being persuaded to trust commercial bank money, via bank transfers, including faster payments using contactless cards, rather than cash in the form of central bank money?” queries Chris Clack, senior lecturer at University College London.

“Can we trust ‘money’ that is just an entry in a bank ledger? What about a large UK bank that has recently suffered major IT problems, or an Icelandic bank that suffered catastrophic collapse?” Clack told New Money Review.

UK bank TSB is being investigated by the financial regulator for a systems failure starting in April 2018 that affected nearly 2 million account holders, while the collapse of Icelandic bank Kaupthing in 2008 involved $45bn and creditors in more than 100 countries.

The debate over risks in fiat currency and cryptocurrency systems seems to be intensifying. Meanwhile, the BIS’s latest anti-bitcoin salvo is further evidence of a philosophical chasm between cryptocurrency supporters and opponents about how monetary systems should operate.