Although the world’s payment and financial settlement networks are rarely in the news, whoever controls them has enormous economic and political power.

As an example, the fact that US dollar payments have to pass through US-based banks allows the American government de facto to cut off states it doesn’t like from the global financial system.

It can do this by leaning on the SWIFT messaging service, which underpins large-value money transfers between banks, securities firms, market infrastructures and corporate customers in more than 200 countries.

For example, backed by powerful US media interests, the Trump administration has announced its intention to cut Iranian banks off from SWIFT as part of a new sanctions regime, despite opposition from some other G8 nations.

While SWIFT is notionally an independent, member-owned cooperative, it has complied with US government pressure in the past. The US says it will take countermeasures against SWIFT board members, their employers or other companies for any failure to boycott the blacklisted counterparties.

So far, almost all large foreign entities, fearful of losing access to the US capital markets and of the scale of potential fines, have succumbed to this combination of threats.

Although control of the world’s wholesale payments system remains in the hands of state-owned central banks, the infrastructure processing transactions in shares and bonds is more widely owned. And it’s in securities settlement that new technologies threaten to loosen the stranglehold of the establishment.

Between the 1960s and the 2000s, the share and bond market’s infrastructure moved from the chaotic, paper-based settlement of trades towards the centralisation of trade processing and ownership information at clearing houses, securities depositaries and custodian banks.

After the financial crisis, the centralisation trend intensified, reinforced by new regulations aimed at reducing systemic risk. But now, proponents of blockchain technology claim that shared ledgers offer a transparent, cheaper and more robust alternative to the centralised system.

In securities settlement, for example, blockchain could save tens of billions of dollars a year for investors by cutting out unnecessary intermediation and speeding up trade processing, say the technology’s advocates. And blockchain could also help to make the financial system safer by removing single points of failure, they argue.

But can the reality live up to the blockchain hype? Are those benefiting from the current market infrastructure likely to support a new system? And could innovation in financial record-keeping come from elsewhere?

An idea whose time had come

The appearance in 2009 of the first cryptocurrency struck a chord with many financial experts.

In Satoshi Nakamoto’s words, bitcoin offered “an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, allowing any two willing parties to transact directly with each other without the need for a trusted third party”.

“By the end of the crisis, the big conversation was about centralisation.”

The project arrived at a time of heightened awareness of the potential risks in a centralised financial system.

Speaking at the recent Blockchain Live event in London, Michele Curtoni, a digital product developer at State Street, remembered the crisis of trust that helped trigger a multi-trillion dollar injection of taxpayer money into the financial system.

Then a risk management specialist at Italy’s central clearing counterparty, CC&G, Curtoni recalls that:

“By the end of the crisis, the big conversation was about centralisation. Everyone was against it, they wanted decentralisation and control of their assets. Most of the calls were from people who said ‘we don’t trust the margin requirements you’ve billed us. We don’t trust, we don’t trust, and so on’.”

Incentivised by a clever combination of cryptography, game theory and economics, the computers participating in the bitcoin network collaborate to produce an effectively unforgeable record of transactions, called the blockchain, extending back in time to the first exchange of value.

Bitcoin also offers anyone the chance to time-stamp ownership data into its blockchain, with obvious applications in recording exchanges of property.

Other cryptocurrencies, like ethereum and EOS, go further and provide a more powerful programming language to network users, allowing them to embed more complex commercial contracts into the currency records.

And yet, despite initial optimism that cryptocurrencies could be used to revolutionise all forms of value transfer, most plans to reform the securities market’s infrastructure so far rely on a diluted version of the new blockchain technology.

This would involve the sharing of share and bond ownership information among a set of trusted financial institutions, many of them lynchpins of the existing record-keeping system, rather than relying on a cryptocurrency network with uncertain provenance, membership and governance.

Public and permissioned blockchains

The word ‘blockchain’ hit the headlines during the 2017 mania in cryptocurrency prices: but defining what it stands for is not easy.

“Blockchain and DLT have become almost meaningless buzzwords.”

“‘Blockchain’ and ‘distributed ledger technology’ (DLT) have become almost meaningless buzzwords that are mainly used for marketing and PR purposes,” say the authors of a new Cambridge University study.

The authors of the study attempt a definition, nevertheless. It focuses on the absence of a single source of truth.

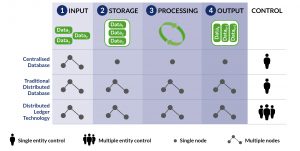

DLT is “a system of electronic records that enables independent entities to establish a consensus around a shared ‘ledger’—without relying on a central coordinator to provide the authoritative version of the records,” say the study’s authors.

From a centralised database to a shared ledger

Source: Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance

The Cambridge blockchain study’s authors go on to distinguish between two very different types of distributed ledger.

On the one hand, ‘permissionless’ blockchains, such as those underlying the two largest cryptocurrencies, bitcoin and ethereum, are open-access and do not rely on any relationship of trust between network participants.

On the other, ‘permissioned’ blockchains involve multiple record producers, who may have been preselected for network membership and who are likely to be bound by some form of contract.

And it’s the architects of such permissioned blockchains—initiatives such as Hyperledger, Corda, Chain and Multichain—that are at the forefront of research into new securities settlement systems.

Closely associated with these initiatives are software developers, such as Digital Asset, Clearmatics and SETL, who are working on the codebases for the new systems.

“Private blockchain initiatives are about established institutions trying to maintain their fee income.”

Unlike permissionless cryptocurrency networks, which have evolved anarchically, the permissioned blockchain initiatives are often sponsored by or owned by the entities running the existing securities clearing and settlement system: stock exchanges, clearing houses, settlement banks and central securities depositaries.

“To some extent, private blockchain initiatives are about established institutions trying to maintain their fee income, while lowering their cost by changing some of the infrastructure at the back-ends,” says Andreas Park, associate professor of finance at the University of Toronto.

The settlement of transactions on permissioned blockchains resembles the traditional financial market much more closely than settlement on the bitcoin and ethereum networks.

In bitcoin, for example, settlement is only probabilistic: there is a small chance of a chain of blocks of transaction data being replaced by another version of history.

Over time, the likelihood of such a change of transaction history becomes rapidly smaller—but there’s a convention amongst market participants of waiting for six bitcoin blocks to be produced (which takes around an hour) before considering a transaction irreversible.

This is one reason why few people consider bitcoin a suitable settlement mechanism for securities trades, which happen at high frequency. However, the bitcoin network might be used to settle high-value transactions in other asset classes like property, where instant processing is less important.

By contrast, the developers of permissioned blockchains emphasise that their networks can be used to assure settlement at a point in time. Confirming settlement finality is a role performed in the traditional financial system by central banks (for money transfers) and securities depositaries (for transfers of ownership in shares and bonds).

Corda, for example, states on its website that “the key challenges for legacy blockchain technology are a lack of privacy and finality. Corda was designed to address these structural shortcomings creating a platform that enables private transactions with immediate finality.”

“Most projects are still in early trial or pilot phases.”

Despite the multiple competing initiatives in this area, many private blockchain projects are still at a ‘proof-of-concept’ stage.

“Apart from native digital assets issued on open, public and permissionless DLT systems, meaningful applications and implementations of DLT systems in production have rarely materialised to date,” say the authors of Cambridge University’s blockchain study.

“Most projects are still in early trial or pilot phases, and it is unclear when they will be mature enough to be live.”

As a test case for the use of blockchain in securities settlement, many observers are paying close attention to a project announced late in 2017 by the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX).

ASX said it was engaging Digital Asset Holdings to replace its entire clearing and settlement infrastructure with a blockchain. The new settlement platform has a target launch date of early 2021.

The prospects for disruption

Given their pivotal role in the global economy, financial market infrastructures like clearing houses and securities depositaries are heavily regulated, often with an effective or even legal monopoly on the processing of trades.

According to some observers, this concentration of power makes it difficult to envisage a situation where a newcomer offering an open-access blockchain overthrows the existing business model.

“There are fundamental problems with a public blockchain transferring legal value.”

“I don’t think it will be a typical story of tech coming from the outside and disrupting the industry,” Robert Sams, chief executive of Clearmatics, told New Money Review.

“It’s too hard to replicate the market structure without industry participation in the new business models.”

There are other, more theoretical impediments to disruption, says Sams.

“There are fundamental problems with a public blockchain transferring legal value,” he argues.

“It comes down to governance. What do you do when there’s a disagreement and the chain forks? You need to keep the law in sync with the state of the ledger.”

However, says the Clearmatics CEO, permissionless and permissioned blockchains may still end up interacting.

“Public blockchains are likely to focus more on the technology infrastructure of the peer-to-peer internet. They are the natural home for self-sovereign identity,” says Sams.

“And the distinction between public and private chains is artificial. In the same way as the internet is a collection of intranets, individual blockchains will be connected in a network of distributed systems. Some will be private and permissioned, others will be open-access.”

Other commentators focus on the possibility of the securities market itself evolving to make use of the new cryptocurrency networks.

“If you imagine that change is going to come via the gradual automation of existing processes, then what’s the incentive for people to automate those processes in the first place? There could be a long lead time and large costs involved,” says Bernard Lunn, chief executive of Daily Fintech, a think tank.

“What’s more likely to happen is that existing assets—whether securities, gold, diamonds or land—get tokenised. And once that occurs, they can be traded and settled in this new way. So I don’t think we’re going to see securities in their current form move gradually to real-time settlement. If you’re crossing a chasm, you don’t do it one step at a time—you have to leap.”

“Show me a system where banks are staking their balance sheets.”

According to Ryan Radloff, chief executive of cryptocurrency tracker provider Coinshares, public blockchains such as bitcoin have one big advantage over the permissioned versions being developed by financial institutions.

“The most important thing for a successful network is the incentive structure,” Radloff told New Money Review.

“In a private blockchain, these structures are not set up so well as in a public blockchain, which pays people all over the world in the native currency to keep it secure. Show me a system where banks are staking their balance sheets. I don’t see a bank that’s going to stake assets on a network that’s unproven.”

“The competitive threat of blockchain to banks is very significant.”

During the first two stages of the modern securities market’s development—paper-based trading and then the centralisation of trade processing at trusted intermediaries—banks dominated the financial infrastructure. But who comes out on top after the current, third stage seems unclear.

Meanwhile, new technology based on the shared recording of financial transaction data may bring about a broader shift in power structures.

In the words of Digital Asset’s chief executive, Blythe Masters, financial institutions are being forced to adapt to the new environment.

“The competitive threat of blockchain to banks is very significant,” said Masters, addressing the recent Blockchain Live conference.

“They will adopt it rather than seeing their business model decimated. History is littered with examples of institutions that have refused to change because change would cannibalise their existing business model. Some great franchises have perished as a result.”

You can subscribe to receive regular content updates on our homepage