Expectations that cryptocurrencies would grant their users complete anonymity have proved wide of the mark. But the debate over digital money and privacy may just be beginning.

[This article is the third in a three-part series covering identity, privacy and money. You can read parts one and two here and here]

Early promises of cryptocurrency transaction privacy…

Bitcoin, launched in 2009, was a new kind of money.

Like cash, and unlike financial assets that are tied to a particular identity, bitcoin can be passed from hand to hand without the need for any third party to approve transactions.But bitcoin also promised to add a huge leap in efficiency compared to traditional currencies.

“For as long as we’ve been tinkering with computers, there’s been a dream of digital cash—something that would be non-traceable, anonymous, instant, free to use and that would interoperate with computer networks,” says Lana Swartz, an assistant professor at the University of Virginia.

“Privacy can be maintained by keeping public keys anonymous”

Bitcoin’s pseudonymous inventor, Satoshi Nakamoto, played up the privacy benefits of the currency in the white paper he or she published at launch.

“Privacy can be maintained by keeping public keys anonymous,” wrote Nakamoto.

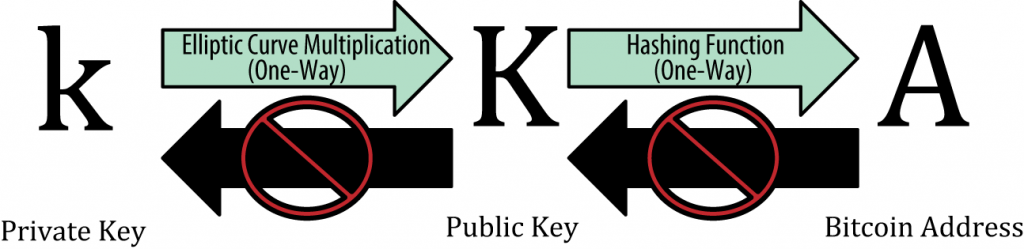

A bitcoin public key is generated, through an irreversible mathematical operation, from the private key that confers ownership of the cryptocurrency. The private key—as its name suggests—must be kept secret to prevent theft of the associated coins.

While bitcoin’s transaction record—its blockchain—is open to scrutiny by anyone, no one will be able to work backwards from a blockchain entry to the identity of the person initiating a transaction, Nakamoto argued.

“The public can see that someone is sending an amount to someone else, but without information linking the transaction to anyone,” he/she said.

A further security step—using a new ‘address’ for each bitcoin transaction—adds another privacy safeguard, Nakamoto noted in the white paper.

A bitcoin address is generated from each owner’s public key via another irreversible mathematical function.

From private key to bitcoin address—two encryption steps

Source: Mastering bitcoin, Andreas Antonopoulos

…proved dangerous to some

Some early bitcoin users took the cryptocurrency’s apparent promise of anonymity at face value in the most provocative way: they used the new payments medium to trade in drugs and other illicit goods.

“Bitcoin,” wrote the Guardian in 2013, “and Silk Road [the main online drugs marketplace] are closely linked.”

“The Silk Road site, which enables users to anonymously order drugs, guns, and more, only takes payments in the digital currency,” said the UK newspaper.

Silk Road and other darknet markets accounted for 30 percent of transactions in bitcoin in 2012, according to one estimate.

“If you get one thing wrong, that’s what compromises you.”

But preventing law enforcement agencies from linking cryptocurrency transactions in dark web markets to real identities has proved much harder than expected.

Ross Ulbricht, the founder of Silk Road, left online traces that allowed US federal agents to uncover his identity. Ulbricht was convicted in 2015 of money laundering, computer hacking and conspiracy to traffic narcotics, and is currently serving a life sentence.

“You’re only as private as your weakest point,” says Matt Odell, a cryptocurrency analyst.

“You can do everything perfectly, but if you get one thing wrong, that’s what compromises you.”

In fact, any attempt to ensure complete anonymity in this digital age may be a pipedream. Jameson Lopp, chief technology officer at cryptocurrency custodian Casa, recently described the complex and exhaustive steps needed to achieve what he calls ‘modest privacy protection’.

“I had to fill out hundreds of pages of paperwork, spend around $30,000 in legal, banking and service fees, and endure a four-month process in order to achieve my goals. I estimate annual recurring costs of over $15,000 for my extreme setup,” Lopp wrote.

“Fundamentally, the ‘crypto’ in cryptocurrency is not privacy: it’s security and authentication,” Lopp told New Money Review.

Linking cryptocurrency addresses to identities

Most of the work of linking past cryptocurrency transactions to individual identities is performed by specialist blockchain analysis companies such as Chainalysis, Elliptic and Coinfirm.

“For-profit companies are trying to deanonymise every transaction they can.”

A recent report suggested that spending by government agencies and regulators on such forensic blockchain analysis—equivalent to mapping the DNA of individual cryptocurrency networks—has tripled in the last year.

“For-profit companies are surveilling the network and trying to deanonymise every transaction they can,” says Jameson Lopp.

Cryptocurrency exchanges, particularly those offering ‘on-’ and ‘off-ramps’—converting cryptocurrencies from and to fiat money—are another key client segment for the blockchain analysis firms.

“Blockchain monitoring software is an essential part of our toolkit,” Obi Nwosu, chief executive at London-based cryptocurrency exchange Coinfloor, told New Money Review.

“We need to have policies and procedures around anti-money-laundering and countering terrorist financing. On the fiat currency side there are long-standing ways of doing this, like sanctions lists. Blockchain monitoring tools provide the equivalent on the cryptocurrency side,” said Nwosu.

Jonathan Levin, chief executive at Chainalysis, told New Money Review how clients such as exchanges and wallet providers make use of his firm’s analyses.

“They are assessing the risk of their counterparty, looking for source of funds and whether a customer received money from illicit sources,” said Levin.

“Our customers have become more sophisticated in detecting patterns of transactions and customizing risk scores per jurisdiction,” he added.

“We don’t want to tip off criminals.”

“Blockchain analysis companies make a determination about a particular cryptocurrency address that is always percentage-based,” says Coinfloor’s Obi Nwosu.

“We take in various bits of information on both the fiat currency and cryptocurrency side and derive an internal scoring metric. If we receive a score on the blockchain side that’s above a certain level we can label it as a certain level of risk,” said Nwosu.

“We can also get guidance from blockchain monitoring companies based on what other exchanges do. They work with various government agencies as well, which also informs their advice.”

However, Nwosu declined to go into detail about how his exchange makes use of the analyses it receives from firms like Chainalysis.

“We can’t disclose details of how we apply this information as we don’t want to tip off criminals,” he told New Money Review.

Discounts on ‘tainted’ coins

Efforts to divide blockchains into ‘clean’ and ‘tainted’ transaction histories have had an effect on cryptocurrencies’ secondary market prices.

Speaking at the recent MJAC/Cryptocompare conference in London, Benjamin Dives, chief executive of the London Block Exchange (LBX), explained how his exchange had recently received a request to sell 8,494 bitcoin (worth around US$3m) via a block trade.

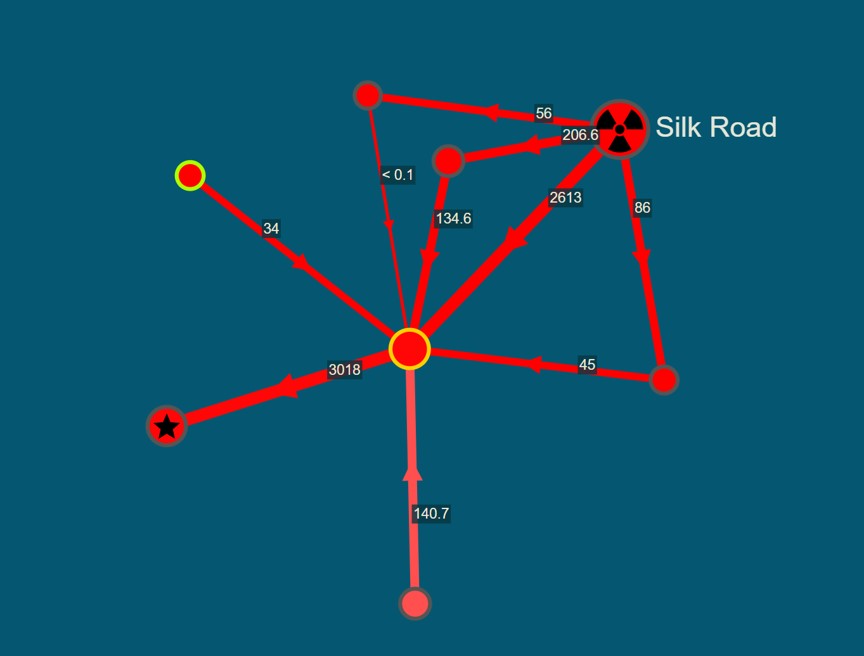

The bitcoin to be sold came from three source addresses, said Dives, one of which proved to be clean. However, the other two could be traced back to a transaction that had involved the Silk Road market, said Dives, who illustrated the provenance of the coins with a chart.

Tainted bitcoins from the Silk Road

Source: London Block Exchange

Reflecting the doubtful origin of the coins, the seller offered a discount of up to 5% of the market price for bitcoin, according to LBX, which declined the trade.

“Someone can try to clean coins by going on a walk through 15-20 other wallets. But the technology allows us to see that,” said Dives.

However, he added, the US government’s stance on cryptocurrencies has been ambiguous.

“What does clean tainted bitcoin is the FBI. They did this when they auctioned off the Silk Road wallets. If the US government had such a strong stance against bitcoin they could have destroyed the coins.”

In 2014/15, the US Justice Department auctioned off the 144,336 bitcoins it seized from Silk Road for an average of $334 each.

“Is one £10 note worth less than another because of how it was used previously?”

Marian Muller, a compliance consultant working with cryptocurrency exchanges, told New Money Review that it should not be up to exchanges to take a view on the transaction history of a particular coin.

“How far back we should go [in cryptocurrencies’ transaction histories] will probably be up to the regulators,” said Muller.

“But for us as exchanges, I would argue it should only be checking the actual depositing addresses. For example, banks only check the identity of the person depositing cash. They don’t somehow trace the cash back three steps to see if it was used to buy drugs a week ago by someone else.”

“This becomes a philosophical question very quickly—is one £10 note worth less than another because of how it was used previously? Should it be? It’s hard to answer a question of how much screening we should be doing without exploring those fundamental questions of what money is,” Muller said.

A taintchain

Others suggest making different use of the ability of forensic tools to trace digital currency transactions far back into the past.

“Efficient coin tracing may damage the fungibility of bitcoin,” said Ross Anderson, Ilia Shumailov and Mansoor Ahmed of Cambridge University in a paper published earlier this year entitled ‘Making bitcoin legal’.

Fungibility means that the individual units of a currency or commodity are interchangeable: in other words, an individual dollar, pound or euro is taken by the currencies’ users as identical to any other.

Rather than using a percentage-based ‘haircut’ or ‘taint’ score for individual cryptocurrency addresses, Anderson, Shumailov and Ahmed propose the introduction of a new methodology to provide more accurate tracing of stolen or illicitly earned coins: a ‘first-in, first-out’ (FIFO) accounting system, where withdrawals from an account are deemed to be drawn against the deposits first made to it.

“Overall, most bitcoin accounts have zero taint using FIFO, while less than 24% escape taint if we use a haircut approach,” say Anderson, Shumailov and Ahmed.

The academics propose the introduction of open-access public ‘taintchains’, calculated using the FIFO methodology, to make stolen or illicitly earned coins visible to all.

They also suggest that cryptocurrencies purchased from regulated exchanges should be regarded as taint-free, but that exchanges should also be required to keep reserves proportional to their trading activities in order to reimburse clients should coins sold as clean turn out to be tainted.

The greatest privacy battles lie ahead

However, the ongoing crackdown on cryptocurrency exchanges and the increasingly intrusive and apparently successful probing by governments and regulators into blockchains may give a misleading impression of the success of law enforcement agencies.

Instead, several developments suggest that the major battles over digital money and privacy still lie ahead of us.

First, there is the accelerating disappearance of cash as a means of payment, a trend that is chipping away at the last truly anonymous form of money.

The likely issuance of government-issued digital fiat currencies will almost certainly pose similar questions about coin provenance as we have seen in cryptocurrencies.

Concerns amongst the general public about revealing the details of all their economic activity to the government and tax authorities may well provide a new boost for non-state-controlled media of exchange.

Second, however successful bitcoin transaction analysis has been, the introduction of privacy-focused cryptocurrencies poses new technological challenges for those seeking to monitor economic activity through blockchains.

“Over the years, the percentage of people using cryptocurrency networks for illicit activity and trying to protect themselves against law enforcement has fallen,” says Casa’s Jameson Lopp.

“However, those that do use them for such purposes are sophisticated and on the cutting edge—they would prefer to use a Monero or Zcash rather than bitcoin.”

Last week, Coinbase, the US cryptocurrency exchange, announced that it would henceforth allow its users to buy, sell and store Zcash, although it would not allow users to send the cryptocurrency to so-called shielded (anonymous) addresses.

Zcash uses a technology called zero-knowledge proofs to allow its users to transact anonymously. A zero-knowledge proof allows a third party to verify that something is true, without revealing any other information.

Third, there is the prospect of large public blockchains like bitcoin or ethereum evolving to incorporate new privacy features, obscuring the link with individual identities.

“Privacy technologies like stealth addresses on Monero, bulletproofs or zero-knowledge proofs on Zcash—are being tested out,” says Matt Odell.

“If one of them becomes successful there will be a fork to package them into a version of bitcoin. And the market will then value the two new forks,” Odell predicts.

“Second-layer networks offer a better opportunity to increase privacy.”

Other privacy enhancements may take place at the layer above the public blockchain, says Casa’s Jameson Lopp.

“The people I know on the technical side would definitely like better privacy in bitcoin: it’s just difficult to do without risking breaking things or greatly reducing the efficiency of the network,” says Lopp.

“That’s why second-layer networks offer a better opportunity to increase privacy without having to change bitcoin itself.”

“For example, the Lightning network has done great work making privacy better,” says Lopp.

“The fundamental topology of the Lightning network means you’re not broadcasting data to everyone. And you’re encrypting packets in a way that prevents other people reading them.”

“A technology called two-party ECDSA allows people to open and close transactions on lightning that don’t look like multi-signature transactions on the blockchain,” Lopp told New Money Review.

“And Layer 2 technology is trying to create channel factories—multi-party channel opens and closes. You could have thousands of people pooling their money to create a single lightning channel. It’s another way of obscuring what you’re doing and hiding in the crowd.”

The application of the discoveries of cryptography to money seems an unstoppable trend. But it still makes some observers very uneasy.

“Anonymity privileges the rich and the powerful at the expense of everyone else,” says technologist Dave Birch.

“And anonymity and self-sovereignty in cryptocurrency sound great if you’re a computer scientist at MIT. But not if your grandma presses a button in an email and sends her life savings to Vladivostok.”

Want to stay up to date with the latest content from New Money Review? Sign up here.