A December incident at the frontier between traditional money and cryptocurrency highlights tensions over access to the global financial system.

Just before Christmas, a cryptocurrency investor and twitter user called @bittlecat caused a stir by revealing he/she had been stopped from withdrawing bitcoin from the Singapore arm of Binance, a large cryptocurrency exchange.

The problem, it turned out, was that @bittlecat had tried to send her funds from Binance to Wasabi, a mixing wallet.

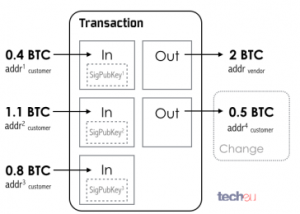

By design, and unlike a bank transfer, a single bitcoin transaction can have multiple inputs and outputs. And Wasabi specialises in ‘coinjoins’, the practice of mixing up those inputs and outputs to obscure the identity of those participating in the transaction.

A bitcoin transaction with multiple inputs and outputs

Source: tech.eu

At the time, Binance said it had blocked the withdrawal because its Singapore arm “does not tolerate any transactions directly and indirectly with gambling, P2P, and especially darknet/mixer sites.” (New Money Review emphasis)

the episode highlights the tightening grip of new regulations targeting the perceived illicit use of cryptocurrencies

After a couple of days @bittlecat got his/her money back after promising not to deal with mixing services like Wasabi any more.

But the episode highlights the tightening grip of new regulations targeting the perceived illicit use of cryptocurrencies.

In June last year, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a group of 36 governments seeking to address money laundering, said it wants to tighten its rules on the transfer of virtual assets like bitcoin.

New FATF guidelines place an obligation on cryptocurrency exchanges—where the general public can convert cryptocurrencies to traditional money, and vice versa—to obtain, hold, and transmit information about their users.

FATF also blacklists two countries—Iran and North Korea—effectively barring them from the international financial system.

Binance told New Money Review that the triggering of a money laundering alert by the attempted withdrawal to Wasabi reflected a Singapore-specific interpretation of the new FATF rules.

“The user (i.e., @bittlecat) had an account with Binance Singapore, which is independently operated with its own policies and compliant with local Singapore regulations, operating under the requirements as set forth by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) and our MAS-regulated partner, Xfers,” Binance said.

“With the anti-money-laundering (AML) and combating the financing of terrorism (CFT) controls set in place for Binance Singapore, the user triggered one of its risk control mechanisms with the transaction,” Binance said.

“We know that stolen funds from hacks and scams are often laundered through mixers”

However, according to Chainalysis, a blockchain analytics company specialising in forensic research of past bitcoin transactions, the approach taken by Binance at its Singapore arm could easily spread to other exchanges.

“While mixers themselves are not illegal, we know that stolen funds from hacks and scams are often laundered through mixers,” Jonathan Levin, co-founder and chief strategy officer, told New Money Review.

“We recommend that our cryptocurrency exchange customers configure Chainalysis ‘Know Your Transaction’ (KYT) to flag large transfers or high-velocity small transfers from mixers for further investigation because it could prevent criminals from cashing out stolen funds,” Levin said.

Tom Robinson, chief executive at another blockchain analysis company, Elliptic, told New Money Review that, after the introduction of the FATF rules, the onus will be on cryptocurrency users to prove that they have earned their virtual money legally.

“The challenge that exchanges face is distinguishing between the use of these services by money launderers or sanctions evaders, and by those simply seeking to maintain their privacy and who are not involved in illicit activity,” Robinson said.

“If an exchange user cannot demonstrate that their crypto-assets have originated from a legitimate source, then the exchange is obligated to take further action.”

However, privacy-focused bitcoin users still appear to have plenty of tricks up their sleeve.

Unlike a bank-issued IBAN number, which identifies the country, bank code, branch code and account number of the bank account holder, a bitcoin address is simply a randomly generated selection of letters and numbers, with no information tying the address to a particular person or institution.

Most people opening an account at a cryptocurrency exchange are now asked to provide proof of their identity. But according to the Open Bitcoin Privacy Project there is still a long list of ways in which bitcoin users can take countermeasures against those seeking to identify them.

And such countermeasures could eventually lead to the impotence of companies like Chainalysis and Elliptic, says Elaine Ou, a former university scientist and blockchain engineer.

“If enough people create transactions where senders can’t be identified from the inputs, then blockchain analysis tools will become like those old-school polygraph tests, where they generate so many false positives that they completely lose credibility and are regarded as junk science, no longer admissible in a court of law,” Ou wrote in a January 4 blog on how to resist censorship with bitcoin.

Seeking to divide bitcoin addresses into those run by the good guys and those owned by bad guys may even prove counterproductive for regulators and law enforcement bodies, says Marian Muller, a financial crime consultant at Bitpliance, an advisory firm.

“I think regulators are trying to force cryptocurrencies into existing frameworks, even when it hurts the overall objective of actually preventing financial crime,” Muller told New Money Review.

“Unfortunately, exchanges are being incentivised to implement rules that protect them from the regulators, rather than actually protecting consumers or preventing crime,” Muller said.

“Most of these regulations don’t really impact the big money launderers, and the resources exchanges use to ‘box check’ regulations would be better suited to finding innovative ways to detect money launderers’ modus operandi. I’m bullish on machine learning solutions, for example, but regulators seem to not like the ‘learning’ part if they can’t control or understand it,” he said.

“Bitcoin in its current state is far from perfectly fungible”

For the time being, associating ‘taint’ with particular bitcoin addresses is likely to continue to cause some coins to continue to trade at a premium to others, say technologists.

“Bitcoin in its current state is far from perfectly fungible,” says Jameson Lopp, co-founder and chief technology officer of Casa, a company focused on building tools to improve the privacy of cryptocurrency users.

The recent border skirmishes between governments intent on ‘lighting’ cryptocurrency addresses and the hackers seeking to oppose them appear likely to continue and intensify.

But far from being cowed by the recent introduction of the FATF rules on virtual currencies, some investors are placing bets that the cypherpunks will win.

“The default setting of the internet is zero privacy”

Dominic Frisby, a journalist, comedian and voice actor, is also chief executive of Cypherpunk Holdings, a company listed on the Canadian Securities Exchange.

Cypherpunk has taken equity stakes in both Wasabi and Samourai, another bitcoin mixer service.

“We think the privacy narrative is going to be one of the biggest stories in technology over the next decade,” Frisby told New Money Review.

“The default setting of the internet is zero privacy. We’ve identified seven main areas of privacy technology and we set up Cypherpunk Holdings to invest across them. Privacy wallets is one of the areas we’ve identified.”

“What’s extraordinary for technology companies like Wasabi and Samourai so early in their evolution is that they’re already making money,” Frisby said.

Wasabi told New Money Review its mixer transaction fees earned between 10 and 14 bitcoin a month ($80-110k at current prices) during the second half of 2019. Cypherpunk has invested $337,500 in Wasabi for a 4.5 percent equity stake, valuing the wallet startup at $7.5 million.

And if governments in any particular jurisdiction made life difficult for the two cryptocurrency mixing firms, said Frisby, they would simply move to somewhere more favourable for their business.

Don’t miss any more New Money Review content: sign up here for our newsletter